- Home

- Marc Alexander

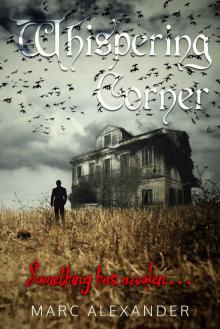

Whispering Corner

Whispering Corner Read online

WHISPERING CORNER

Marc Alexander

© Marc Alexander 1989

Marc Alexander has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988 to be identified as author of this work.

First Published in 1989 by Arrow Books Limited under the pseudonym Mark Ronson

This edition published in 2016 by Venture Press, an imprint of Endeavour Press Ltd.

Table of Contents

Prologue

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

EPILOGUE

A NOTE FOR THE CURIOUS

For

Louisa Mary Alexander

Prologue

This is the last book I shall write.

It will not be aimed at faithful readers who have an appetite for my brand of horror fiction; it will never be submitted to my agent who gave me up in understandable disgust; it is to be solely for myself — an act of catharsis.

It will be written without literary considerations, though I shall endeavour to recall — with an author’s word processor memory — some passages of the novel I was engaged upon while an occupant of Whispering Corner. My aim is solely to set down the events which cast me in the role of a character in one of my own more macabre stories.

At the moment these events and their implications are so chaotic in my mind that only by cataloguing them do I believe I shall be able to achieve a sane perspective of what led up to the ultimate tragedy. This is being attempted in another world — almost another time — from the Dorset woodland where I fulfilled a dream by buying that queer old house, where love came unexpectedly, and a unique combination of creative imagination and the paranormal laid upon me the terrible burden of belief.

Because of the daytime heat which hangs like a curse over this coast I shall type through the hours of darkness, but if there are times when illicit alcohol brings release or I cannot bear to face the still-menacing past I have the consolation that for the first time I am free from the tyranny of a deadline.

Perhaps when this self-imposed task is completed I shall be able to come to terms with both the way my career has ended and the horrific situations I once inflicted upon my characters. Perhaps as an exercise in expiation it will free me from the dreams which continue to haunt me on this far shore. Mostly, however, I believe that this narration will enable me to decide whether or not I am guilty of murder.

Jonathan Northrop

1

Twin patterns of light flared on the rain-spattered windscreen, killing the driver’s vision and panicking him as the maroon Peugeot rounded a curve in the forest lane. When the wipers momentarily cleared the glass he saw an orange Mini angled in a ditch so that its headlights not only raked him but transformed the ancient trees on either side into a monochrome tunnel.

Silhouetted against the halo was a swaying figure whose arms moved in a slow-motion attempt to flag him down.

Braking too hard, he felt the big car slide on mud which had been washed over the potholed tarmac. The swinging beams of its lamps transformed the silhouette into a young woman, and the driver had a fleeting vision of a face white like a clown's and framed by long fair hair. He closed his eyes, braced for the sickening thump as she vanished beneath the bonnet. But the tyres gripped and the world steadied.

He elbowed open the door and ran through the downpour to her, and could not help but notice the erotic way her wet blouse clung to her breasts — a guilty reaction doused by the sight of blood mingling with raindrops on her temple.

‘Please help me,’ she murmured. ‘It came out of the woods.’

He caught her as her legs buckled …

*

The ratchet of my Olympia — a well-worn relic from good old Fleet Street days — made an ugly sound as I tore the paper from the roller and thrust it into a wastepaper basket already crammed with failed attempts to get my overdue novel under way. Yet again, I knew that what I had just written was a lousy intro.

I prowled the flat, impatient for the Cona to heat coffee and wondering whether it was too early to have a proper drink to settle my panic. I am embarrassed to admit that I once described a character in one of my stories as feeling ‘as though a hand of ice had fastened on his heart’, yet that was how I felt that morning. It was not just the intro; I was finally admitting to myself that the storyline of my proposed book Ancient Dreams was as trite as the opening I had been agonizing over, and I feared that as a novelist I was finished.

The truth was that I was having my first bout of writer’s block.

It was something I had derided in the past when I believed I would run out of time before I ran out of words. But now I was unable to get to grips with a novel that should have been half finished, a situation which had caused me to lie to my darling agent for the first time in our association. I dared not let her think I had lost the confidence gained back in ’83 when for several euphoric weeks my Shadows and Mirrors headed the top ten fiction list.

Following that halcyon period, I really believed I was capable of producing bestseller after bestseller, until it became apparent that my next novel had not caught the public’s imagination in the same way as Shadows. Now I needed Ancient Dreams to reinstate me, yet I knew it would be almost impossible to deliver the script to the Griffin Press on time. Furthermore, Griffin had just been taken over by a big publishing conglomerate, and its new masters were less likely to be lenient over a late delivery than my editor Reggie Burnside, who had become a personal friend.

The reheated coffee was too bitter. I poured a shot of Courvoisier and turned it into a longish drink with Perrier water. The noble spirit had its usual reviving effect and I determined to start yet again — and this time get it right.

I returned to my work table under the window, but stood for a minute, glass in hand, gazing at pale spring sky above the rooftops on the opposite side of Coram Square. Our flat was the second storey of one of those Georgian houses that once gave such grace to Bloomsbury and had somehow survived the planners and developers who had entered into an unholy alliance to turn this once romantic neighbourhood into something out of Orwell. It was the sight of the new leaves like green mist about the square’s old trees which prompted the Imp to whisper that what I needed was a stroll out of doors to get myself ready to tear into my work.

I must explain the Imp.

One of the curious things I had found about writer’s block was that when I had psyched myself up to the point where I was eager to hear my typewriter’s reassuring rattle — woefully missing on today’s electronic machines — I would find a pretext to delay getting on with it; there would be some household chore that became suddenly urgent, an errand to be undertaken then and there so it would not interrupt the creative flow once it was in spate, or a long neglected telephone call that had to be made at once. I had code-named this syndrome the Imp of the Perverse, with acknowledgements to the master of my craft, Edgar Allan Poe.

Of course I had tried to analyse it.

To have blamed the problem I shared with Pamela would have been easy, but I refused to consider such a glib explanation. I have no time for men who use their marital situations to excuse lack of effort in pursuit of their self-proclaimed creative goals. Besides, our unspoken tensions had not affected the writing of Shadows.

If I had an inkling of the real origin of the Imp, I kept it locked in the lumber room of my unconsciou

s along with the other bric-a-brac of life which I preferred to ignore. I admit that I am a coward when it comes to facing unpleasant realities and will always avoid them if I can. Perhaps I was successful in writing escapist literature (with a very small l) because I am an escapist.

But this morning my desperation to get the wretched book started was stronger than the blandishments of the Imp.

I fed a sheet of A4 into my machine and resolutely began typing. I had accomplished half a page when the telephone chirruped and I heard the lively voice of my agent Sylvia Stone, quite rightly known as Sweet Sylvia by her authors.

‘Just ringing to remind you that we have a lunch date,’ she said.

‘But that's on Friday.’

‘Today is Friday, old chum. Authors!’ She sighed theatrically. ‘Come on, descend from your ivory tower and get to La Capannina as fast as you can. I only hope that your vagueness is because you’ve been working your unmentionables off. How many pages?’

‘You know I never number my pages until the end.’

Sweet Sylvia laughed dutifully at the old joke.

‘But you are up to schedule?’ she persisted. ‘Now that Griffin is part of Clipper Publishing the days of wine and roses are over.’

‘It’ll be all right on the night,’ I muttered.

‘Better be. Now hurry. I’d like to have a drink with you before the Mount-William arrives.’

In less than an hour I was in the streets of Soho, skirting knots of out-of-town football fans clustering round electronic porn parlours. In my long-gone journalistic days when Soho had been part of my beat, real girls had stood in the doorways; somehow that seemed less sordid than video peepshows and snuff movies. Then an AIDS poster reminded me how our sexual mores are changing and protective taboos emerging, as they did for the Victorians under threat from non-curable syphilis.

This train of thought, prompted by the fact I was in Wardour Street, reminded me of a film producer I had once worked with on a documentary film who, at a predictable stage of intoxication, would burst from the gay closet in defiance of his sober lifestyle as a husband and father. I could imagine the fear this new plague brought him, and the dilemma it created in his relationship with his wife. Perhaps celibacy had something to be said for it after all. One gets used to it.

At the corner of Greek Street and Romilly Street was La Capannina, a restaurant which had long been a favourite of mine and one which I had used as a setting in Shadows. Knowing my preference, it was typical of my agent to choose it for this meeting for which she knew I had little enthusiasm. Gianni greeted me warmly, and his wife Linda smiled. ‘The lady is already here, Mr Northrop,’ she said. I was led from the foyer into the restaurant, where Sylvia was sitting in a favoured scat by the window with a Punt e Mes before her.

‘Hello, Jonathan,’ she said as I joined her. ‘I was hoping you would have a packet of manuscript under your arm for me.’

I reminded her that true artists never show half-finished work and quickly ordered an aperitif. If Sylvia Stone had not inherited the Hermes literary agency which her father had founded for daring young writers in the thirties, she would have made an excellent headmistress. She was tall and had never rounded her shoulders to hide the fact. Her soft greying hair was swept back and her complexion, which had never known cosmetics other than a modest touch of lipstick, must have been the envy of women half her age.

Publishers liked doing business with her because she was utterly reliable and nearly always cheerful. Her grasp of literary agreements was awe-inspiring, and should any contracts department attempt to palm a tricky little clause into the small print her tone could become as chilling as a Siberian wind. Her authors she regarded as a family whose oddly assorted members she encouraged, played mother confessor to and, if necessary, bullied. On occasion she had been known to send ginseng to those who were-flagging but at a publisher’s party, after a little too much sparkling Piat d’Or, I heard her remark, ‘Old spinsters like me traditionally end up with cats or very nasty little dogs, but I have authors. Sometimes I wish it had been nasty little dogs.’

Although she greeted me with her usual bright smile, I was aware of her surreptitious glance of concern. I became conscious of the dark circles under my eyes; in fact I had been a little shocked at the haggard face which had peered back at me from my shaving mirror that morning.

‘Ready for your exodus to darkest Dorset?’ she asked.

‘The house is almost ready. It hasn’t been lived in for over a year, and it was a hell of a mess. A local handy lad named Hoddy has been doing a sterling job on it.’

‘And Pam?’

‘She’s staying on in New York for a bit longer.’

‘She must be enjoying it.’

For a moment neither of us could think of anything to add to that particular topic.

‘I thought our boozy lunches with dear old Reggie would have come to an end when Clipper took over Griffin …’ I began.

‘Officially it was a merger.’

‘In the same way that Jonah and the whale was a merger. Anyway, what’s the scenario for today?’

‘Reggie wants to introduce you to Jocasta Mount-William. Now that she’s editorial director of Griffin as well as Clipper she’ll be a very important lady in your professional life.’

‘And Reggie?’

Sylvia shrugged.

‘Although he’s been given a fancy new title, Jocasta is in fact his boss. Entre nous, he’s desperately looking around. He’d been promised a seat on the Griffin board before the merger, but now …’

For a few minutes we gossiped about the merger and the personalities involved, and how smaller publishing companies were being ingested by the big ones, and who was likely to end up where in the endless musical chairs of the publishing world.

Suddenly Sylvia laid her hand on mine.

‘Jonathan, when you talk to Jocasta Mount-William sound what you are — a confident bestselling novelist. I hear that as far as Griffin is concerned she has the new broom syndrome, and I gather that her taste does not encompass the sort of popular novel that Griffin has specialized in — especially horror novels.’

‘She’s an intellectual?’

‘Cambridge degree in literature, old chum. Her claim to fame is that when she was with Icarus Press she actually made Barram rewrite the opening chapter of Marl before it went on to win the Russell-Montgomery award.’

‘Oh great,’ I said. ‘But what’s a nice high-brow girl like her doing in the bordello of popular publishing?’

‘She has the reputation of being very, very efficient, has friends in high places, and I think her brief is to raise the tone of Griffin Books by a few notches. So if she asks you about your motivation as a writer don’t go into your “too lazy to work, too scared to steal” routine.’

‘It got a laugh on LBC.’

‘Just remember that today it’s Radio 3. Ah, here’s Reggie.’

Reginald Burnside was a balding young man in a very well cut suit including a waistcoat and a magenta open-necked shirt, a sartorial style he had acquired while scouting for books on the west coast of America.

‘Hope I’m not late for my favourite literary agent — and author,’ he said. ‘Sylvia, Jonathan, I’d like you to meet Jocasta. She’ll be looking after you now that I’ve been banished to non-fiction.’

The young woman beside him reminded me of a newspaper picture I had once seen of a female freedom fighter (or terrorist), though on closer inspection I saw that her olive battle fatigues could have only come from the King’s Road. Her sun-streaked hair was cropped short, her long face was over-tanned and she wore glasses that were ever-so-slightly tinted blue. Her watch was very expensive, a diver’s Rolex.

‘We meet at last. I’ve heard so much about you,’ said Sylvia in her best agent’s manner.

Jocasta set the tone immediately. She gave Sylvia a mouth smile and said, ‘You’re with the Hermes Agency.’

‘I am the Hermes Agency,’ Sylvia replied in h

er extra pleasant voice.

‘Of course. It’s just that there seem to be so many agencies these days.’

‘And fewer and fewer publishers …’

Sylvia’s voice was honeyed, the sort of honey that comes from a Venus fly trap. But I also knew that, whatever was said to ruffle her, Sylvia, for the sake of her authors, would never lose her cool.

There was a truce while the menu was discussed and I extolled the delights of the restaurant’s cheese pancakes.

‘So you’re the author of Shadows and Mirrors,’ Jocasta said musingly as she handed her menu to the waiter. ‘Somehow I had the impression from your book that you’d be younger. Oh well … I hope you have something worthwhile coming up for us.’

‘Jonathan’s superstitious about talking about his work until he’s typed The End,’ Sylvia explained. ‘But when it’s delivered I’m sure you’ll have another bestseller on your hands.’

Jocasta looked doubtful. ‘I hate to be a prophet of doom,’ she said, not hating it at all, ‘but I checked the sales figures of your last book before I left the office, and they’re very disappointing.’

‘Early days yet,’ I said.

‘I’m afraid there has been enough time for our sales people to gain an idea, and frankly …’

Her voice trailed off as the hors d’oeuvres arrived and Reggie gave me an encouraging wink.

‘The trouble is that horror is becoming passé,’ Jocasta continued as she deftly speared a tiny dead creature with her fork. ‘Shadows and Mirrors came out at the right moment. Now the public wants something different. Something like Martin Winter’s Blue Hour. We’re having phenomenal success with that.’

Sylvia said, ‘Martin Winter, and good luck to him, is having phenomenal success because he’s basically a film writer and he turned one of his scripts into the book-of-the-film, a film which had the good luck to be a hit at Cannes. With all that publicity it follows that the book should be a blockbuster.’

Whispering Corner

Whispering Corner